Changing Society Briefing 2: More single people, lower fertility rate and changing family structures.

- Joe Saxton

- Nov 29, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 28, 2025

Introduction

This is the second in the Heyheyjoe briefing series looking at external social, economic, and demographic changes and their impact on charities and non-profit organisations. This one focuses on household and family structures in four specific intertwined areas: the rise in numbers of single people, the declining fertility rate, the divorce rate, and the overall structure of families.

Rise in the number of single people in the UK population

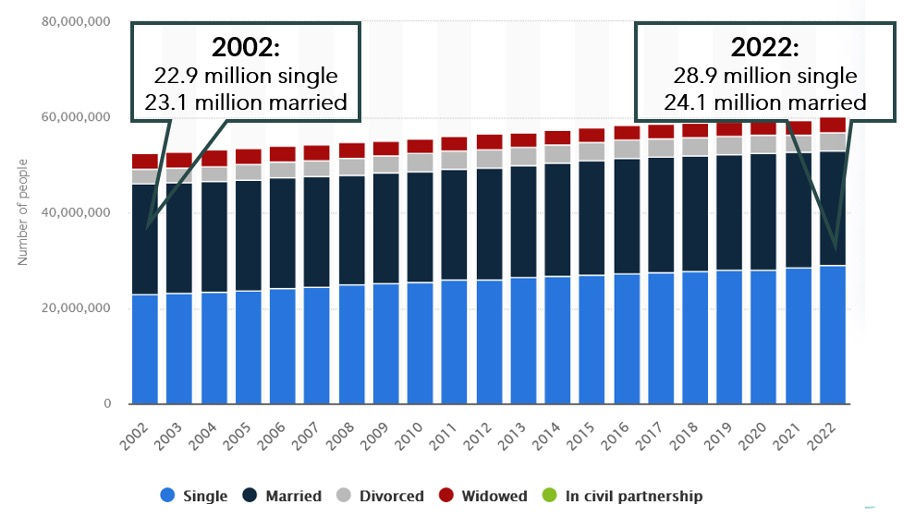

Chart 1 shows the number of single, married, divorced, widowed and civil partnership people in the population between 2002 and 2022. The main take-out from the chart

is the growth in single people by approximately six million over a 20 year period. There are a number of reasons for this. People are living longer, and women tend to

Chart 1: Changing household structures in the UK population

live longer than men. Secondly, people marry later so most people now in their twenties are single when a generation ago they might have been married. And lastly people are choosing to be single. The social pressure to marry is much less than it used to be, so people are tending to stay single both as a lifestyle choice and because they can’t find the right person. In an age of online dating, its never too late to partner or marry, so people don’t need to rush.

The growth in single people bring a need for more houses. A couple takes up a house or flat, but so does a single person: so more single people means more houses are needed even without an increase in population. More single people mean more leisure and holiday activities as people spend their salaries on themselves and not bigger mortgages for bigger families. Its worth saying that some of those single people, may well be single parents too.

Decline in the typical (or total) fertility rate in UK women.

The typical (or properly called total or TFR) fertility rate for women is at an all-time low. As chart 2 shows its currently at around 1.5 ie a woman typically has 1.5 children. This is below the replacement rate of 2.1: a couple needs to have 2.1 children to replace themselves and keep the population stable. So with the current fertility rate the UK population will shrink without immigration, and more children will be an only child than was the case a generation ago. We are not alone in these changes. South Korea has a TFR of 0.7 and China around 1 (and Nigeria’s is over five in case you were interested).

Chart 2: Changes in the total fertility rate in the UK 1938 to 2023

Declining number of marriages and divorces

Chart 3 shows how the number of marriages is declining: from about 400,000 in the seventies to around 200,000 today. The number of divorces has also declined both in absolute terms and as a percentage of the number of marriages, it used to be around 50%, but it’s now around 40%. The decline is possibly due to a number of factors, but I like to think its down to online dating being a better way to find a soulmate!!

Chart 3: Number of marriages, divorces, and the divorce rate since 1942

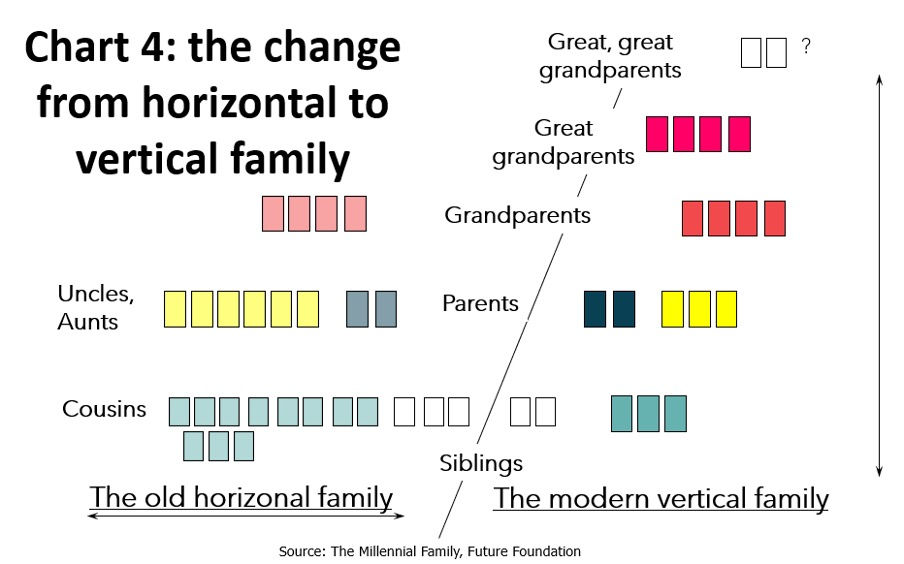

Changing family structures from horizontal to vertical to any-way up

The decreasing number of children, the rise in single people, the declining fertility rate and the high divorce rate has an impact on family structure. In the 1930s, 40s and 50s family structures were typically horizonal as chart 4 shows. Children had a large number of siblings, cousins, uncles, and aunts, and possibly some grandparents. The family was broad in numbers terms for each generation, but didn’t cover many generations. As people lived longer, and couples had less children, the number of siblings, cousins, uncles, and aunts that a child had decreased, while the chances of having grandparents, great grandparents and even great great grandparents increased. The family became tall and narrow ie vertical.

On top of this, the forming, fracturing, and reforming of families gives rise to siblings having step siblings, stepcousins, step grandparents and so on. A parent may go from being in a couple, to being single, to being in a couple again. I called this the any-way up family. Families are no longer traditional or stereotypical, and come in a huge breadth of shapes and sizes.

The rise in single people and the changing shape of families have a number of implications for children and their parents. Its take more energy, and more money proportionately to be a single parent. A single person or a single parent is less resilient to changes in finances, such as an increased mortgage rate or losing a job. There is only one salary to pay the bills, not two. Children’s emotional needs can get lost or be damaged, in families that separate, or where parents reform new partnerships.

The implications for charities

What do all these changes mean for charities? Firstly for the impact on services, and second for the impact on giving and volunteering.

Reduced individual financial resilience.

The rise in single people mean more households with a single income, not a joint income. Single income households are more vulnerable to financial shocks, such as losing a job, interest rate rises and cost of living increases. This means there are likely to be more people who need the help of charities with debt and financial management. And probably more people with mental health challenges arising from greater financial uncertainty who need the help of charities, and the lack of emotional support that living alone may tend to bring.

Reduced collective financial resilience.

As well as the decreased individual financial resilience that comes from more single people, fractured households, and smaller families, is the reduction in collective financial resilience. In other words charities will find their clients and beneficiaries collectively struggling when inflation increases, or benefits aren’t keeping pace with inflation or being withdrawn. So expect an increase in issues on which charities need to campaign: for example the winter fuel allowance, and the introduction of universal credit: because there are more vulnerable people out there.

Increase in emotional needs of adults and children.

Wherever there is financial stress on individuals, there is emotional stress too. So as more people are living in poverty, or likely to live in poverty, there will be more people who are probably going to need mental health support (and probably physical health support given that stress causes physical health problems too). So charities can expect to see people with more mental health needs, more benefit support, and a variety of other problems that come from poverty, old age, living alone, homelessness and children with an unstable home life.

Less spare cash for giving. Less time for volunteering

In a household where one person pays the mortgage or rent there is less spare cash for charities – because the costs of two people living together are only marginally more than one person, but the income is typically doubled or at least likely to be increased. Equally the amount of time and capacity that a single person, particularly a single parent, has to volunteer is reduced in a one-person household.

So on the money and time fronts, a population with more single people, with fractured and reformed families and with a smaller extended family is probably going to mean less giving and volunteering.

Less legacies 20 years from now

As house prices rise, and the ratio of the average house cost to the average salary is ever greater, then people will buy houses later and later in their lives. They need to save for a bigger deposit, particularly if they are a single person, and they will have a bigger mortgage for longer. The combination of these factors means that people will have less (net) capital in their houses by the time they reach retirement. More of the capital they do have will need to go on supporting their children and possibly paying for the residential care of their parents.

So once legacies from the current baby boomer generation is replaced by people who were born in the late seventies, eighties and nineties expect legacy income to decrease.

Less young people in the workforce

As there are fewer young people (because fertility is decreasing), and the costs of buying houses requires larger and larger incomes, then why is any young person going to work for a charity. Indeed how they are going to afford to work for a charity? This demographic and economic challenge is compounded by another change. Companies and social movements are in the market for doing good. People no longer need to work for a charity to do something worthy. So they can earn a good living and feel good about themselves, without the need to work for a charity.

This briefing is part of a series looking at the impact of social, economic, technological, and demographic changes on charities and non-profit organizations. We have already published a briefing on the ageing population, and in future issues we will look at the impact of digital, rising government debt, wealth distribution and falling levels of religious conviction on charities. Go to www.heyheyjoe.info for more information.

Joe Saxton

November 2024

Comments